A Tale of Two Sisters

Mary, Martha & the matter of feminine worth. Is there really a better part?

“We are love, and we don’t have to earn or prove or deserve this fact. And if we can recognize that we’ve never been separate from it, and bring it forth outside of us, this is what saves us.”

― Meggan Watterson

Truth has never been so elusive. This is an inconvenient reality that greets us not just in the daily news but when we are deep in deciphering Mary Magdalene’s story.

It remains remarkable that across all four canonical gospels Jesus was anointed by a woman—a detail that could not be deleted. The sketch of the story is there, hidden under edits and redactions that resulted in the anonymization of the anointing woman, of whom Jesus stated, “throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her.”

Yet, how does one proclaim the memory of a nameless woman?

For a moment, imagine the anointing woman as plainly incognito and inclusive of every negative detail that the Gospel of Luke lays upon the scene. Even then, the anointing woman presents us with an picture of immense courage:

She strides bravely into a sea of masculinity, where she is unwelcome to perform this sacred ritual, criticized at every movement. Rather than freezing, she allows her emotions to flow freely, weeping quietly. We may not know the reason for her “maudlin” tears, that are to become synonymous with Magdalene in the Middle Ages, but it is clear that her vulnerability is the birthplace of her bravery.

Whatever her intentions or the meaning of the way she addressed Jesus with this holy oil, the anointing woman rises from the ashes of confusion whenever we go looking for Mary Magdalene.

So, let us consider the long-held possibility: was Mary Magdalene the anointing woman? The idea that Mary anchored this defining moment, which transforms Jesus into Christ, is not as far out as it may seem.

It was a tradition so deeply seated in early Christianity that for someone like Pope Gregory, Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene being one in the same was a fact—plain and simple.

1400 years later, some scholars look at the text itself, with the clear indication that Mary Magdalene’s full name is not present in any anointing scene, as all the proof they need to parse these characters entirely. Some feminist theologians have supported the notion that separating the four anointing women is the simplest means to clearing Magdalene’s from the sexual shadow and the negativity that surrounds it.

This is a tempting course of action to restoring the legacy of Mary Magdalene. Yet, moving in this direction risks creating an unintended glass ceiling around her potential as a feminine leader and greater significance.

If Mary Magdalene was the anointing woman, it would mean that she was one-in-the-same with Mary of Bethany, a figure found in one story in the Gospel of Luke and in two stories in the Gospel of John. In both accounts, Mary of Bethany is inextricably tied to her sister, Martha—in more ways than are traditionally considered.

Martha is yet another female figure in the story of Jesus we take at face value, rarely going beneath the surface of what the pulpit or the legends tell us about who she was. But, when we dig into the matter of Martha, down to the details, new information arises. In that process, it seems easiest to isolate her from Mary, thereby segregating her into a version of femininity that’s often judged or overlooked.

Yet, if we choose a metaphorical lens that seeks to unite all the fractured voices of women’s worthiness, then other possibilities come to light around the famous duo of Mary and Martha that are of profound significance to the story we’ve been told.

Sister Sister

While tradition held that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene were the same person, the two are never clearly connected in the Bible you may hold in your hand.

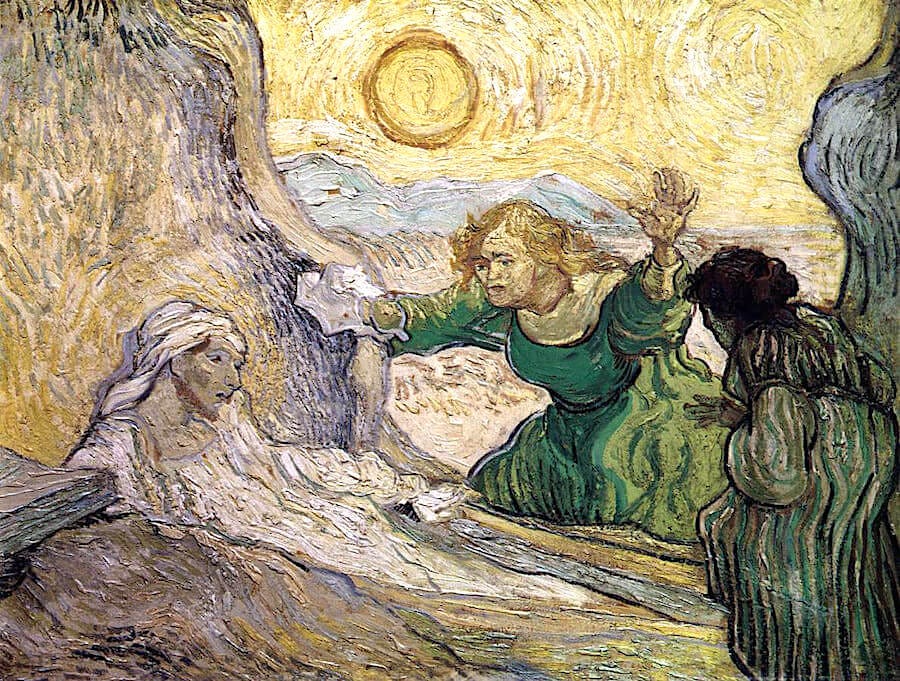

Mary Magdalene appears 13 times across the canonical gospels, most often at the death, burial, and rising of Jesus, and once before hand in Luke. Mary of Bethany appears in three stories, all during Jesus’ ministry—a scene in her and Martha’s home in Luke, the Jesus raising her brother Lazarus from the dead in John, and the anointing scene, also John.

When church father Irenaeus proclaimed all four gospels must only be read together, the stories of the sisters of Bethany became muddled amongst each other—just as he intended.

These women are pivotal figures in Jesus’ story, involved in key moments such as Mary’s anointing of Jesus as Christ, Martha’s “Christological confession” of verbally proclaiming Jesus as Christ, and the famous scene with their brother Lazarus—one of Jesus’ most powerful miracles on record.

Bethany, the purported town they inhabited (actually called Al-Eizariya “the place of Lazarus”), became a pilgrimage site as early as the Crusades in the Middle Ages, when Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem, purchased the village and built a Benedictine abbey there named for Martha and Mary.

A century later, the Golden Legend, a compilation of stories on the lives of saints, was published by Jacobus De Voragine, the archbishop of Genoa. This tome recorded and amplified legends of Mary Magdalene and Martha as her sister, that had been long held in folklore and told orally for arguably centuries.

These are the tales Magdalene seekers know well—the sisters and company arriving in a rudderless boat on the shores of France, Mary living out her life teaching and praying in the South of France, and Martha going on to slay dragons (quite literally).

The gospel stories held in the Bible date from at least the second century, but the sisters we see in John and Luke appear vastly different. Scholars searching for clues as to whom the sisters were have concluded that, as usual, the written record entwining the sisters of Bethany was predated by oral stories.

In Martha from the Margins, Allie Ernst demonstrates that Martha was a figure of authority, particularly in the Johannine community (followers of the Gospel of John), but her stories were widespread and significant before they ever made it into paper (or papyrus).

A “far richer fabric of traditions woven around this figure” held that Martha was present at the tomb of Jesus with Mary Magdalene and even attended the Last Supper. Ernst paints a picture of a widespread Martha tradition that transcended John or Luke, with her as a resurrection witness in the Ethiopic and Syrian texts.

Ernst emphasizes that in early Christianity:

“Martha is charged with a great deal of authority in some early Christian texts, to the point that she is called not only the ‘apostle to the apostles’ but also ‘a second Peter’.”

This is a level of rivalry of Peter traditionally recognized between him and Mary Magdalene and a key in the Mary-Martha puzzle we will return to.

Even in the emerging Western Church, Martha shows up prominently in the work of church father Hippolytus of Rome, and his rendition of the Old Testament Song of Songs (also called Canticle of Canticles)—a sacred love poem known for its erotic qualities.

Hippolytus blends non-canonical traditions with canonical ones, possibly drawing upon oral stories, with explicitly Greco-Roman mythological references, and consistently elevating Martha to place her alongside not just Mary of Bethany, but Mary Magdalene.

At first glance, his rendition of Song of Songs reads as borderline absurd, with two women (Mary and Martha) in a romantic scenario where they pine for one man (Jesus): “I have found whom I love and I will not let him go.” The creative license Hippolytus takes with the ancient archetype of hieros gamos (sacred marriage) begs an odd question:

Are we reading about Jesus in a scene of menage-a-trois meets polygamy, or is this a brilliant literary device that speaks to us allegorically?

Maybe (at least this) church father knew something about the nature of who Martha was that has been lost and misunderstood in all the strangeness.

What if Martha and Mary—as Hippolytus imagined—were one in the same person as Mary Magdalene, in that each individual woman is simply a reflection of the whole?

We understand that this idea may seem as absurd as a three-way-love-poem written by a man known to be sexually repressed. Therefore, we ask: was Martha was an expression of a facet of Mary, who too is a woman emblematic of the expression of the divine feminine in Jesus’ story?

Lady of the House

Even within the narrow scope of the canonical gospels and what they have to say about Mary and Martha, clues are apparent in details typically overlooked.

We meet Martha in Luke chapter 10, verse 28, when Jesus is deep in his traveling ministry, performing miracles. He takes a rest stop at a village, “where a woman named Martha welcomed him into her home.”

That Martha is called by her personal name and not tied to any man as a wife, mother, daughter, or sister is remarkable. It is, emphatically, her home—a controversial detail, because there is evidence on both sides of the argument when it comes to the contemporary rights of women. While Jewish scripture forbade women from possessing property, evidence exists for female home ownership in the New Testament and beyond—but either way, Martha’s authority isn’t a typical scenario.

Continuing with Luke’s brief but impactful story, Martha had a sister “called Mary” and the famous scene is painted of Mary sitting at Jesus’ feet, listening to his teaching while Martha busies herself with the tasks of cleaning and serving. Martha approaches Jesus and pleads for him to help her motivate aimless Mary: “Tell her to help me.”

Jesus replies, “Martha, Martha,” a double-edged sword of potential endearment and chastisement, then goes on to tell Martha that she is “anxious” and it is Mary who has “chosen the better part” by listening to his teachings.

This scene sticks out like a sore thumb in the way Jesus calls Martha’s name, echoed later in the silly Brady Bunch scenes of Jan saying, “Marsha, Marsha, Marsha, always Marsha!” Two sisters, pitted against one another, one receiving praise and recognition (Marsha/Mary) and the other feeling forgotten (Jan/Martha).

“Martha, Martha” reminds us of the Wedding at Cana in John where Jesus harshly calls to his own mother, “Woman, what does this have to do with me.”

We wonder—do these scenarios accurately reflect how Jesus spoke to women near and dear to him?

As we shared in Immaculate Deception, Luke’s account of women is questionable, but this scene in particular raises more questions than it answers. Furthermore, it leaves us with a distinct sense that Luke’s author was carefully crafting these scenes to highlight negativity around female characters.

Luke’s version of events, with putting the words “the better part” in Jesus’ mouth, had serious consequences for the treatment of women. Only in the last century, with the rise of feminist theologians and scholars like Barbara Reid’s (Op PhD), have we been able to clarify the biased perspective that may have driven this pivotal scene with Martha and Mary.

A Family Affair

To untangle the similarities and differences of these scenes, and therefore better understand who the sisters of Bethany were, we must jump to the two stories of John’s they feature in.

(To note, scholars generally believe that John was written or compiled after Luke, and John is generally considered the “outlier” gospel, different from the other three “synoptics,” so named for their similarities.)

In John 11, we meet Lazarus of Bethany who is “ill” and from “the same village as Mary and her sister Martha”—notice that they are of the same village, not household, and Mary’s name precedes Martha’s. Next, there is a foreshadowing to the following chapter John 12 with the anointing scene: “This Mary, whose brother Lazarus was ill, was the Mary who anointed the Master.”

In sum, the sisters send a message to Jesus that “the one you love is ill,” referring to Lazarus.

Jesus comes quickly as “Jesus loved Martha and her sister, and Lazarus,” confirming the intimacy of the relationship between Jesus and this family (a repeated theme).

Jesus even has to argue back to his disciples who lament that going to Bethany means retracing their footsteps—so, what was so important to him about Lazarus and his sisters? Martha runs out of the house to greet Jesus, Mary stays at home, and this is when the pivotal Christological confession happens—more on this in a moment.

Only after that statement does Mary of Bethany enter the scene, repeating the same words Martha had said, “Master if you had been here my brother would not have died.”

Mary of Bethany weeps, Jesus weeps, everybody weeps. Many fail to notice that Mary of Bethany does not weep during her anointing of Jesus in the following chapter—but Luke’s nameless anointing woman does cry, and as mentioned, Magdalene is very often portrayed as tearful in art.

These are details that are easily glossed over but matter deeply. No one believes Jesus is capable of this miracle, but his faith in himself and God never falters—Lazarus walks straight out of the tomb, wrapped in burial clothes.

Moving forward a chapter to John 12, we enter the anointing scene, with Martha hosting a dinner with Lazarus and Mary seated below Jesus, blessing his feet with spikenard perfume. Here, Judas is the one to argue with Jesus over the pricey potion (in Matthew and Mark it’s the disciples who take the position of the questioner, in Luke it’s the Pharisee).

Jesus says “leave her alone,” as he notes that this oil will be used for his burial too.

Just after this scene is when Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, fulfilling an ancient Hebrew prophecy of the Messiah’s path—an indication that this anointing of “Christ,” the Greek word for “Messiah,” was a peak moment.

In sum, we know that Mary and Martha are sisters, living in a town of Bethany, apparently sharing a home in Martha’s name, who are likely wealthy and independent. They follow Jesus and have a level of intimacy with him where he “loves” them.

Their dynamic reads like a family affair, because from tears to accusations, they are comfortable being vulnerable and honest with each other.

John’s gospel has long been thought to have deep layers of symbolism and meaning written into it, from the stories highlighted to the hidden patterning in the text, as detailed in books like the Genius of John: A Compositional-Critical Commentary on the Fourth Gospel by Peter F. Ellis and The Good Wine: Reading John from the Center by Bruno Barnhardt.

When you layer these elements together, even going beyond John 11 and 12 into John 20’s famous scene of Mary Magdalene and the risen Christ in the garden, it feels as though John is transmitting a truth to us about who Mary was that Martha’s presence overshadows.

The Matter of Martha

Philosophers and scholars have spent millennia debating the role of Martha, Mary of Bethany, and Mary Magdalene in the context of feminine leadership in the church. Whether we realize it or not, the feminine portrayals have had a direct impact on all women influenced by Western culture—this is why “Martha” matters.

In Immaculate Deception, we detailed the way that Luke’s rendering of women, namely his anointing woman story, impacted the legacy of Mary Magdalene and well beyond. We relied heavily on Reid’s brilliant analysis in her book, Choosing the Better Part, and a reference to the praise Jesus bestows on Mary—now, let’s look further at Martha, in particular.

Martha embodies action and Mary contemplation, a dichotomy that has been preached from pulpits ad-nauseum for centuries.

The positive side of this presentation is the way that Jesus gives us all a permission slip to set aside our mundane tasks in favor of cultivating our relationship with God. Yet, all too often this story has been used for priests and pastors to push the silencing of women, an agenda embedded in Christianity’s patriarchal culture.

Questions abound, from the way the women are pitted against each other in comparison, judgment, and favoritism, to the nature of Jesus’ message in this moment.

Why doesn’t this compassionate leader, who supports all those downtrodden, have greater words of support and empathy for Martha? So often women identify with Martha, as we struggle to juggle all the demands of life from work, to personal relationships, to the household, to being a mother, partner, and in Martha’s case, sister and hostess.

Reid writes:

“From such a stance, there is no good news from a Jesus who not only seems indifferent to the burden of the unrealistic demands but even reproaches one who pours out her life in service.”

In this moment, we remember how the stories of Jesus were spoken aloud in communities, passed down for generations in Aramaic and Hebrew before being written in Greek, and then translated, edited, and re-transcribed through centuries. The first versions we have of these gospels all date to no earlier than the second century—a truth that forces us to admit what we would rather not: no one fully knows what Jesus actually said, or did.

Is Martha and Mary’s conflict in Luke a true representation of an incident from the life of historical Jesus? Or, does it reflect the need to resolve a tension around the role of women in the community Luke’s author was writing for? As we suggested in Immaculate Deception, could Luke have been drawing from an earlier source, written or oral, that portrayed women in a more positive light?

What if Luke’s author twisted the narratives to limit the authority and prominence of women in his own account?

The Better Part

The emerging Church, for their part, took Luke’s story as we know it and ran with it, heaping praise on the humility of Mary sitting at Jesus’ feet.

For Augustine of Hippo, Martha and Mary represented the Church—Martha, the present Church which “receives the Lord into her heart”; Mary, the future Church which “shall delight in Wisdom alone.” Origen commented how “action and contemplation do not exist without one another.” Then, there’s Hippolytus, who placed Martha in a scene that she does not exist in—chapter 20 of John where Mary Magdalene (not Mary of Bethany) sees risen Jesus in a garden.

While John’s Mary and Martha of Bethany are not as clearly pitted against one another as they are in Luke, traces of comparison remain in the depiction of these women.

This is especially clear in John 11 when Lazarus is raised. Martha runs out of the house to greet Jesus, again in an animated role, whereas Mary hangs back at her home, emotional, quiet, and being comforted by friends and neighbors. Active and passive, their roles in John 11 mirror their roles in Luke 10.

Next, each sister cries out to Jesus in the same way, a curious detail in which their despair borders on accusation, (paraphrasing) “if you were here, this wouldn’t have happened!” In addition to the closeness demonstrated by how the sisters address Jesus so informally, there is the issue of how their words are identical to one another—a peculiar indication that textual critics have picked upon.

Even more intriguing is the way the scene ends, in John 11:45, with no reference to Martha, only Mary:

“Therefore many of the Jews who had come to visit Mary, and had seen what Jesus did, believed in him.”

To briefly address John’s anointing scene, Martha and Mary are again put in the roles of active and passive, mundane and spiritual, as Martha serves and Mary performs the anointing ritual. A significant, if mysterious detail, is the way Mary anoints Jesus’ feet, not his head, which would be traditional for the ceremony of a king or priest.

We wonder: is Mary’s choice of Jesus’ feet a show of humility or an editorial deflection to diminish the power of the event?

These are the subtle details that point to the power struggles woven into the fabric of these pivotal moments where Martha and Mary seem to carry archetypal roles of women manifested in two forms.

What this reveals is that these women have been used as tools to direct the role of all women within the church since its infancy.

When it comes to the feminine embodiment of Jesus’ teachings, is there truly a better part to choose? The question continues—how did human hands of gospel authors, church leaders, and even scribes shape Jesus’ divine message over time, often for political reasons?

Textual Instability

P66 is an unassuming set of letters and numbers that sits at the center of a mystery around Martha’s presence and significance in John’s gospel.

Martha is surrounded by what expert Elizabeth Schrader Polzcer, PhD, calls “textual instability,” and Polzcer’s meticulous, groundbreaking research demonstrates that Martha may not have been present in copies of John that predate the second century.

To zoom out and rewind for a moment, all ancient texts were copied and transcribed on a regular basis due to the simple fact that papyrus disintegrated and ink faded relatively fast. Scribes were responsible for making these copies, and deviations in the text naturally occur throughout history–Bible and otherwise. P66 (Papyrus Bodmer II), discovered in 1952 near Dishna Egypt, is a codex containing only the Gospel of John dated to around 200 CE and it is well known for having a squirrelly scribe.

Polzcer painstakingly shows how Martha’s presence is fraught with issues, with “instability” plaguing not just P66, but one in five Greek manuscripts, and one in three Old Latin ones.

Everyone was getting nervous about what to do when writing Martha in!

Examples include unexpected omissions of Martha’s name entirely, “Mary” being changed to “Martha,” “Mary” appearing instead of an expected “Martha,” a clear change to nouns, verbs, or pronouns around the sisters of Bethany, and a different person named first among those whom Jesus “loved” in John 11:5. Further, changing the names was simple because “Martha” and “Maria” in Greek are only different by one letter.

Polzcer makes her interpretation of her findings clear:

“Martha was added to John’s Gospel in order to discourage readers from identifying Lazarus’ sister Mary as Mary Magdalene, an identification that was happening in patristic and extracanonical literature as early as the third century.”

We first discovered Polzcer’s edits through a viral sermon by Diana Butler Bass, “All the Marys.” You can listen to it here:

Radical as it may seem, Polzcer is not the first to believe that Martha was written in with the intention of obscuring the significance of Mary.

Allie Ernst, author of Martha in the Margins, names Eugene Stockton, Marie-Émile Boismard and Arnaud Lamouille, Gérard Rochais, and Jacob Kremer as scholars who have posited that Martha’s presence may have been added later and there was only one sister from Bethany in John’s original storytelling.

Can these discrepancies be dismissed as mundane and innocent scribal errors?

Doubtful, posits Polzcer. For one, it was often the same scribes who easily and correctly transcribed the sisters of Bethany in Luke 10 from one papyrus to another, who then “produced variants” when it came to copying the same names in John.

The chance that it was all a minor mistake declines when considering the long-standing tradition that equated Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene. Further, many early Christian thinkers, orthodox and gnostic, believed that Mary Magdalene was from Bethany, and “Magdalene” was a moniker solely (as we discussed in The Power of a Name).

Polzcer theorizes that the Mary edited out here is Mary Magdalene and this action was taken specifically to obscure her identity. To make sense of how John and Luke connect, Polzcer believes the Bethany sisters from John are in Bethany, whereas elements of Luke point to the sisters of chapter 10 being from Galilee or Samaria—her theory is that these may be two different families.

Why was Mary of Bethany not called Magdalene in the text? Many reasons exist, including that her identity was purposefully being shielded.

In a way, it makes sense—we notice how the scenes with Mary of Bethany occur in the intimate personal space of her home and family, a place where so many of us are called simply by our first names. If Magdalene was an honorific title, it is logical and plausible that her title would be used when she was outside of her home and rather her first name only be used within it.

Another possibility along these same lines is that Mary may have earned the title “Magdalene” later in time, perhaps after she anointed Jesus as Christ, making her the Christ-Maker.

The lingering question, after considering Polzcer’s consequential findings, is:

How does this shift the power dynamics around the sisters of Bethany and the way their examples have implications for the spirituality authority of all women?

Christ Proclaimer

One of the most influential moments across all four canonical gospels resides in the voice of Martha in John—the Christological confession.

In Matthew, Jesus asks the disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” Peter responds, “You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God.” Jesus speaks one of the most famous lines in all of Christianity: “I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock, I will build my church.”

This is a high point, recorded across the synoptics, and used as the basis for apostolic authority from the earliest days and up until now in the Catholic Church. John does not record a similar event with Peter, and instead contains an almost identical confession of faith in chapter 11—spoken by Martha, when Jesus has come to raise Lazarus.

Jesus then says, “I am the resurrection and the life; he who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and whoever lives and believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?” Martha responds: “Yes, Lord; I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, he who is coming into the world.” Her words are almost verbatim the same ones that Peter has spoken.

Why is the Christological confession so important?

It quite literally holds the key to St. Peters—this is the “rock” that the Church built its case upon to create the institution of hierarchical power that claims absolute control over the teachings and legacy of Jesus Christ.

To put the Christological confession in the mouth of a woman is significant, on its own.

If we look at the picture of Martha being painted in the text—chastised in Luke, never named at the crucifixion or resurrection scenes—it makes little sense that she would be the one to speak in this pivotal moment.

Martha’s feminine Christological confession becomes an anomaly at best, a footnote at worst—when all the gospels are bound together, diminished under Peter’s rising authority.

But was Martha the one to speak these crucial words to Jesus? Or was it Mary of Bethany, who also anointed him in John?

The earliest clue comes from Tertullian, the second-century church father, who mentions in his writing that Mary, not Martha, speaks the Christological confession. Echoing this indirectly, St. Ambrose in the fourth century mentions how “Jesus loved Lazarus and Mary,” no Martha noted. Fast forward to the present day, Polzcer believes that based on her research, it was Mary of Bethany who was the original “confessor”—not Martha.

If it was John’s intent for Mary Magdalene to speak the Christological confession in John 11:27, this would suggest that her leadership role in John was akin to Peter’s in the Gospel of Matthew. This possibility is not so far out when held side-by-side with repeated claims in gnostic texts that Mary Magdalene and Peter rivaled each other in power.

In the Gospel of Mary, Peter critiques and doubts Mary’s vision of Jesus and transmission of his teachings, and Levi comes to her defense: “but if the Savior made her worthy, who are you to reject her? Surely the Savior knows her very well.”

If we look at the canonical gospels, there is a clear tension in the post-resurrection scenes—who saw Jesus first? In all four, the women are at the tomb first. In Mark and Matthew, Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene initially, but in Luke, Peter is the one who has the real interaction with the risen Christ before anyone else.

This matters here because if the resurrection scene echoes the Peter—Mary comparison, then it would make perfect sense for the same juxtaposition to be present with the dualing Christological confessions of Matthew and John.

But if Church authority is at stake, edits would need to have been made to elevate Peter and minimize Mary, laying the matter of leadership amongst these two and their followers to rest.

Further, and unsurprisingly, Polzcer has identified the same “textual instability” surrounding Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene, because in early manuscripts, discrepancies and “anxiety” are clear amidst scenes that feature Magdalene in the canonical Gospels. Polzcer suggests this “editorial activity,” is problematic, because it creates “real exegetical consequences,” meaning that these slight deviations had serious repercussions for the interpretation of the role of Magdalene in the Biblical account.

Polzcer says:

“This surprising intersection of instability around a character in all four Gospels should make us question our certainties about who Mary Magdalene was, and devote more attention to all gospel story variants that feature her.”

If Martha did not belong in John, we are brought back to the question about where she came from in the first place. Was the story of the sisters of Bethany in Luke 10 always present? Did John’s author, or later scribes, take the character of Martha and add her into his story—and if so, why?

None of these options seem to make much sense, especially given Ernst’s research that demonstrates an oral tradition of Martha seemed to exist outside of and possibly predate both of the gospels.

The point of confusion seems to hinge upon the assumption that these stories were literal accounts of historical events.

If we can shift our perspective, even slightly, to view these women and their roles as literary devices with allegorical meaning, then what other answers emerge around a tale of two sisters and their entanglement?

What’s in a Name?

This conundrum of where Martha came from dips us into “chicken or the egg territory”—is she from Luke? From John? An oral tradition? A literary device?

It does not seem that a clear-cut answer about Martha’s origins is feasible, but if we are willing to question everything, then addressing her name itself raises unexplored (as far as we know) questions.

“Mary” is the most abundant feminine name in the New Testament, appearing 54 times in 49 verses. As we noted in The Power of a Name, an Israeli historian named Tal Ilan undertook the staggering task of surveying all ancient documents to poke at the question: how prevalent was the name, “Mary,” really, in the first century Hebrew community?

Out of 317 names she pulled together, 80 of them were “Mary,” and 62 “Salome”–she pointed to the popularity of Miriam the sister of Moses in the Old Testament and the historical princess Mariamme I, a wife of Herod the Great, being the impetus for Mary’s commonality.

Linguists believe that “Mary” comes from the root “mer” or “mery” meaning “love” or “beloved.” In Hebrew, “Miriam” is connected to the root “mr,” meaning “bitter” or “mry,” meaning “rebellious.”

Reid points out that “Mary” may also be linked to the Hebrew noun, “mrym,”meaning “height” or “summit.” St. Jerome famously translated “Mary” as “drop of the sea” leading to the title for Mother Mary (“Star of the Sea”) and “Maris” is a Kabbalistic (Jewish Mysticism) title for “mother”—pointing to the very ancient name for all prominent mother-goddesses, “Queen of Heaven.”

“Martha,” on the other hand, seems to be a derivative of “Mary.”

Some sources say “Martha” means “lady” or “mistress of the house,” a description that seems to derive from the Bible rather than predate it, because the signature of Martha in Luke and John is that she serves and commands her own home.

Digging deeper into the etymology, “Martha” is connected to the root, “myrrh,” just like “Mary,” and the verb, “to be bitter,” just like “Mary.” Whereas Mary has etymological meanings, Martha has few, most tied directly to the name Mary which in part could be explained simply by their common root “Mar.”

Yet, one of the more curious parts of the P66 edits Polzcer identified is a prime reason it was so easy for the scribe to switch Mary’s name to Martha’s—in Greek, “Maria” to “Martha” is just one letter different. An “iota” is easily changed to a “theta,” without much notice.

Is there any possibility that “Martha” the name is not unique but a derivation of the name "Mary?” What would that mean for who Martha (the figure) might be and the potential that all we are examining is, at its core, symbolic?

Again and again, there is a subtle theme that even the church fathers suggest—the closeness of the sisters may not be something for us to untangle but for us to fully understand on a metaphorical level:

What if Martha and Mary are two sides of the same coin, cleaved from one another for the purposes of telling a more compelling story?

This may seem outlandish but it is a very simple solution that solves all the so-called problems around Martha and Mary—including the way these names were used to diminish themselves, each other, Mary Magdalene, and the authority of all women.

Inherent Worth

Who was Martha?

Was she a very real first century woman and friend to the living Jesus Christ or an allegorical archetype representative of a human facet of the divine feminine wholeness?

Martha continually has served as a representative of what is human, from her description in John and Luke, to how artists have portrayed her over the centuries.

She embodies our busyness, our desire to be “good,” the shame we feel when a loved one chastises us, and the fear deep in our hearts when our family member is ill.

Martha remains quietly in the background, but also proclaims her faith with a confident and pure heart—she embodies seemingly paradoxical forces that any honest person can easily identify within themselves.

In the Gospel of Mary, Mary rallies the troops, so to speak, when the disciples are in a moment of despair. She says:

“Let us praise his (Jesus’) greatness, for he has prepared us for this, He is calling upon us to become fully human.”

To be “fully human” is a concept unfamiliar to traditional Christians and the Greek word it comes from is “anthropos.” Jean-Yves Leloup, a translator of the Gospel of Mary, describes anthropos as wholeness—complete within its form, integrated of left and right, masculine and feminine, of spirit and of earth in a state of harmony long understood by indigenous and ancient cultures.

At the end of this text, when Levi speaks up for Mary, he infers that it is through being “fully human” that the “Teacher takes root in us.”

What if Martha was showing us that pathway all along—one where we must embrace our humanness to fully open to and connect with the divine?

If you are accustomed to taking everything at face value, to doubt the veracity of Jesus’ words can seem sacrilegious. But what if Luke’s rendition of Jesus in this pivotal moment was wrong?

Embracing our humanity means integrating the “Martha” and the “Mary” within us, and there is no “better part” on a path to becoming whole.

Since we view Mary Magdalene as the embodiment of a great feminine spiritual story we desperately need, then Martha cannot be rejected—even if she is not physically present in certain texts we have been conditioned to believe she is in.

Whether or not Martha is historical or figurative, she represents a facet of our humanness we must not overlook or dismiss if we are to fully heal and integrate, especially given all that has been hidden for the sake of power and control.

Ultimately, if Mary and Martha are expressions of the feminine long repressed that mirror energies within us all, then we are called to listen closely to hear these lost voices emerging from the sands of time with a story about the Love that we seek—but already are.

Share with your Mary Magdalene friend

We would love it if you would share The Magdalene Thread with a friend who you know would resonate with our message or who just adores Mary Magdalene. We are so grateful for your readership and support!

Sources

Choosing the Better Part? Women in they Gospel of Luke by Barbara E. Reid

The Gospel of Mary Magdalene by Jean-Yves Leloup

Hippolytus between East and West: The Commentaries and the Provenance of the Corpus by J.A. Cerrato

Hippolytus’ Commentary on the Song of Songs in Social and Critical Context by Yancy Warren Smith (2009)

A homily of Gregory the Great and Mary Magdalene (Text of Homily 33) by Roger Pearse (2020)

Is Martha an Interpolation into John’s Gospel? by Tommy Wasserman, Evangelical Textual Criticism (2019)

Martha and Mary: It’s Not That Simple, by Christopher M. Bellitto, Catholic Digest

Martha: A Remarkable Disciple, by Robin Gallaher Branch, Biblical Archeological Society (2023)

Martha from the Margins: The Authority of Martha in Early Christian Tradition by Allie M. Ernst

Martha, Peter’s Equal, by Gordon Lindsay, The Bible’s in my Blood Blog (2014)

Mary or Martha?: A Duke scholar's research finds Mary Magdalene downplayed by New Testament scribes by Eric Ferreri, Duke Today (2019)

Mary the Tower by Diana Butler Bass

A New New Testament: A Bible for the Twenty-first Century Combining Traditional and Newly Discovered Texts, compiled and edited by Hal Taussig

Was Martha of Bethany Added to the Fourth Gospel in the Second Century? by Elizabeth Schrader Polczer, Harvard Theological Review 110:3 (2017)

What do the Church Fathers say about Martha and Mary? by Nicholas Senz, Aleteia.org (2019)

Woman with the Alabaster Box by Shane Clayton, Wandering Stars

Read our full source list:

Living Resources on Mary Magdalene

Welcome to a treasure trove of diverse perspectives on Mary Magdalene, and all her legend and legacy touches.

I cannot think of God as a man, it’s unnatural. God should consist at least of both and then there’s the beyond possible, the imminent and transcendental. All creation and creatures come out of a woman, the universe and its material come out of a womb, no man can get pregnant. When I was 7 years old I left the Catholic Church, it left me numb and incomplete, there was no appeal to a living experience and I went on a search. I found an answer but still more and more questions unanswered, and it’s good I will never find an answer. God after all is the mystical experience in which you have to disappear and nothing is left behind of all identity and memory. Unio Mystica can only through a woman, a mother. Strange fact, men at the moment they’re dying call after their mother, so do men and women during torture. I came in contact with the goddess mother Kali during my six year stay in a mystical school in India 45 years ago. Kali is the female founder of the universe and of her children, which we all are and to which we return when we die. I read a book about a Saint Ramakrishna who lived a century ago, and he loved, chanted and served the mother Kali his whole life, but nothing special happened until he met Tottapuri, a wandering monk, he destroyed the image of Kali, the mother as the last hindrance to merge, to become one with God. The physical union with a woman is the key to open the door to the metaphysical. I cannot think of celibacy ever taking a man and women to God, and that’s why I’m convinced Maria or Martha had also a physical bound with Jesus, as a human and as a child of the goddess mother.

I stumbled upon your site and I'm glad I did. While reading the first part of this post, I kept wondering what Libbie Schrader Polzcer might have to say. Glad to find her cited numerous times. In August of this year I had the unbelievable blessing of bringing Dr. Polzcer to my church for her presentation on MM. She had actually been baptized as a child in my little Episcopal parish. I am excited to learn more about Mary the Toweress both historically and metaphorically. So relieved to find out that God isn't interested in keeping women in their place after all. Linda S. Clare at The Deep End.