Immaculate Deception

Restoring Mary Magdalene and Jesus' female followers from the margins of the Gospel of Luke's masterful storytelling

“And I tell you, ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives, and the one who seeks finds, and to the one who knocks it will be opened.”

—The Gospel of Luke, 11:9-10

When we choose to believe that words written and crafted by human hands come directly from the divine, and are therefore infallible, it inherently creates a knot that complicates any attempt to separate truth from fiction.

Dare we ask:

Who wrote the books bound together as the Holy Bible?

It is well known that the gospels modern Christians know as Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were circulated as oral stories and anonymous texts for decades before being marked with the names we associate them with. Creating “the canon,” also known as the approved list of sacred texts included in the Holy Bible, was a long and very human process–politics, agendas, biases, and natural flaws included.

Around Mary Magdalene, the pendulum swings back and forth, with a schism in the middle.

Some of Mary’s advocates stand within the realm of Christianity and biblical scholarship–this includes a wide range of opinions from the normal dismissals of her relevance to renegade feminist scholars elevating her to new heights. Yet, many within the Church will only take their questioning and curiosity so far–there is a felt sense that if you speculate or poke holes in too much of the history and doctrine, it becomes dangerous territory.

On the other end of the spectrum are spiritual seekers who tend to sidestep the deep murky waters that surround Christian history and the Bible itself, following other pathways of knowledge and understanding. We believe that all narratives, stories, ideas and perspectives are not only worthy of investigation, but that each holds clues and magic to uncover, even if found unseen in the margins.

The secrets we seek are hidden in the texts–all of them. Even what we wish we could dismiss holds opportunities for deeper reflection, especially when it comes to Mary Magdalene. This is why we believe that examining her portrayal in one of the most revered scriptures in Christianity–the Gospel of Luke, the only gospel to name Mary Magdalene before Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection–is essential work for any true Magdalene follower.

There is more than meets the eye with the author of Luke (who we will call “Luke” from here on out)–often lauded as “a friend of women” simply because this text includes more references to all women than others.

Rather than ignoring or disdaining this text, which marked Mary Magdalene with elements that led to the pernicious prostitute rumor, investigating Luke leads to a revelation of how and why Mary was diminished in the text–a potentially true story stranger than fiction.

The Infallible Four

The question isn't who was Luke, because it is widely acknowledged that “Luke” was not the author of the gospel that bears his name. The inquiry that precedes authorship must be how and when the gospels were identified.

Irenaeus, a Bishop of Rome based in Lyon (ancient Gaul, modern France), was the first in recorded history to mention the gospels by name–and not until 180 CE, well over a century since the death of Jesus’ and any eye witness accounts.

This was a time of dividing the wheat from the chaff, separating heretic from true believer, and Irenaeus was one of the Church fathers leading the charge.

His five-volume work “Against the Heresies,” written around 185 CE, was a take-down of gnosticism, the early Christian school of thought that led the believer on an inner spiritual pathway.

What is known is that the canonical gospels are not named for their actual literary authors, though they were long associated with the direct apostles of Jesus. Justin Martyr, another anti-heretical Christian writer, referred to the texts simply as apostles’ “memoirs.” Tying the apostles who followed Jesus in his lifetime to the emerging hierarchy of the Church through the sacred scriptures was a powerful way to increase clerical authority—the basis of apostolic succession.

Not only was Irenaeus the first to refer to the canonical gospels by name, he was the first to insist on four gospels being the center point to the canon–with an arguably “pagan” reason behind the number four. To him, this specific quantity of gospels represented the “four zones of the world in which we live” and “four principal winds”–ideas that connect to more ancient concepts, such as the four directions and the four elements of creation.

Ireneaus insisted Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, above all the other gospels circulating, were perfect truth–specifically when held all together. He rejected the use of individual gospels calling it heresy, for example the Valentinian gnostic’s preference of the Gospel of John and the Marcionite use of a “mutilated” version of Luke.

Irenaeus was right on one count: when you disentangle the four gospel stories’ from one another, carefully evaluating each one and all its unique idiosyncrasies, the truth emerges naturally–the one he perhaps intended to hide. When it comes to Mary Magdalene’s legacy, two canonical gospels stand out, above the rest: John* and Luke.

Luke’s name came to rest on this text for the first time in Irenaeus’ own writing, a full century after most scholars believe this gospel was initially recorded on papyrus.

If Luke wasn’t the true name of the gospel’s writer, who penned this well-crafted and highly impactful canonical gospel?

Every author has a lens through which their work is filtered, conscious and unconscious, and often with a specific intention and agenda. Revealing what we can about who “Luke” was illuminates the landscape from which this gospel—so impactful to Mary Magdalene’s legacy, emerged from.

Paging Doctor Truth

Contemplating the possibilities on who Luke’s author was leads us into a deeper mystery, because the version of this gospel we have now is in a form different from the original. Following this trail, you end up within the niche realms of biblical scholarship, where fluency in Greek is required, and experts spend years holding every text side-by-side, including gospels you have never even heard of.

Marcion, one of the leading gnostic Christian thinkers of the second century, had a gospel of his own most often referred to as the “Gospel of the Lord” or the “Gospel of Marcion.” In fact, he was the very first to create his own “canon” collection of texts, which included his preferred gospel and eleven of Paul’s letters–and excluded the Old Testament.

One of the pressing questions for scholars in this field centers around whose gospel came first: Marcion’s, Mark’s or Luke’s—an inquiry part and parcel in the quest to understand who copied whom.

This is a rabbit hole of ancient intrigue, the kind that surrounds Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene, in that the truth–if we are honest–is something we can never fully know.

What surfaces from the swirl of the unknown is that the gospels we have now are later versions of the originals. These books were born of stories and ideas first spoken, then written down, then copied and edited, moving through a long list of (masculine) hands.

The primary author of Luke, as we know the gospel today, seems to be a well-educated gentile (non-Jewish) Christian who was writing for a predominantly Gentile community using Greco-Roman literary forms. He** admits, in the text, that he was not an eyewitness to the events he accounts, while emphasizing the care with which he has investigated the tradition that he passes on.

There has long been speculation about whether Luke’s author was one in the same with “Luke the beloved physician” mentioned in Colossians, one of Paul’s letters in the Bible. It is true that Luke expands on descriptions of illnesses in healing stories in a way that is unique, and that some manuscripts of this gospel lack the derogatory comments in Mark about doctors. Another complication to the Luke-as-physician claim is that Colossians was not written by the Paul himself. Thus, the case for certainty on this possibility of “Dr. Luke’s” authorship is not strong.

Acts of the Apostles, the book of the Bible directly following the gospels, is generally believed to be written by the same author as Luke. This opens another realm of possibilities about who Luke’s author may have been, but conviction remains elusive upon a closer examination of Acts itself, which is a veritable “can of worms.”

While Acts claims to tell its tales on the apostles in the years after Jesus’ death from a seat of great authority–being written by a traveling companion of Paul, many have pointed out that its narrative simply does not stand up to examination.

This argument is built on a long list of reasons, leading scholars believe that Acts is an entirely fictional account. It must be stated that Acts of the Apostles was one of many in the same genre of literature from this time period–including The Acts of Paul and Thecla, the Acts of Peter, the Acts of Thomas—the list goes on.

This is the kind of nitty-gritty work that happens when you step foot in the territory of the authorship question. All the points are wobbly in and of themselves when you take into account the cultural context and scribal translations.

Yet, this conversation holds juicy details about the true messiness of early Christianity—how little we actually know and how prominent figures that stand cloaked in mystery may have been instrumental in the creation process of the Bible we now have.

Accurately Anew

To stand on more solid ground, it’s important to know that while Luke is usually grouped with Mark and Matthew, and referred to as the “synoptics,” it is very different in tone, style, and content–especially the treatment of women and Mary Magdalene.

Most scholars believe Luke relied on Mark as one of his primary sources, yet there are 230 sayings common to Luke and Matthew, but absent from Mark. Many experts also believe that the gospel authors used a hypothetical written source dubbed “Q,” but it seems as though Luke had sources unique to him, including a potential document referred to as “L.”

It is clear that the Gospel of Luke is not the product of pasting together material from other sources. Rather, it was carefully composed to convey the good news of Jesus Christ and shaped with a particular audience in mind.

Precision was his stated intention, expressed specifically in the first lines of the gospel that he undertook the project with the aim of “investigating everything accurately anew, to write it down in an orderly sequence.”

By ancient standards, Luke is an excellent historian. Although he was likely a gentile, he layers in context about Judaism and ancient Hebrew people that brings Jesus’ story to life and honors the culture it emerged from. Luke’s vocabulary and literary style indicate a refined education, with arguably the highest mastery of the Greek language seen across New Testament texts. Moreover, Luke is a skilled storyteller, who crafted his narration with the desire to console, guide, and challenge his faith communities, especially common people.

Many of the most famous stories of Jesus are unique to Luke’s account–such as Jesus’ infancy, from the Annunciation of his birth to his Mother Mary and (aunt) Elizabeth to the events that play out in the Christmas story. Tales of impact and legacy that are found in Luke only include the Prodigal Son, the Good Samaritan, the Pharisee and the Tax Collector and the Rich Man and Lazarus. This gospel holds a wide cast of characters, with over a hundred unique individuals showing up throughout, from high ranking aristocrats and rulers like the Herod family to crowds full of ordinary people–fisherman and farmers.

Stories are staggeringly powerful and arguably shape the world we live in, wrapped as we are daily in our minds of beliefs and thought. Narratives give form to our imagination, finding expression in literature, art, and everyday conversations.

As the famous saying goes, history is written by the victors—but it’s the compelling storytellers that stand out above them all.

Across the landscape of Western and religious history of mankind, Luke easily reaches the heights of one of the most famous and talented storytellers. Even standing alone, without the rest of the Bible, his words craft a vivid picture of Jesus’ life and character, told in a way that evokes our senses and emotions. To this day, rituals, beliefs, and practices at the heart of Christianity derive heavily from Luke’s interpretation of the story.

One unique aspect of Luke has been explored by feminist scholars in recent years, and that illuminates Mary Magdalene, is the portrayal of women.

Luke is known for bringing scenes in Jesus' life into sharper detail, bringing forth names, origin stories, and legacies left fuzzy in other accounts. Women appear more in his gospel than any other text in the New Testament.

The question arises, especially with a feminine lens: what was Luke’s intention around how his narrative wove in the women in Jesus' life?

What does his account, so “thoughtfully” written by such an adept reality-crafter, offer for the female figures, and women’s agency, authority, and equality?

Quality Not Quantity

On the surface, Luke’s quantity of women seems to point towards a positive inclination of the feminine. He mentions 13 women not spoken of elsewhere in the Bible. He includes lengthy scenes between women, such as the annunciation to Mother Mary and the exchange between the sisters of Bethany. He frames women and men together. In 18 different places, Luke adds a woman to a scene where there is only a man present in Mark’s gospel.

If Luke was focused on accuracy, lauding his own attention to detail, and more highly educated than all other gospel writers, then what does this mean for his inclusion of women?

A natural assumption, based on Luke’s stated depth of research, would be that he was factually accurate–women had a prominent role in Jesus’ story. The following thought would be: Luke must have had access to other sources with more women included that the other gospel writers did not have—or chose to exclude.

It is well known that books of the Bible were often written to answer lingering questions in the centuries after Jesus’ death about what happened and what we should believe about it all. This “question answering” mission was the primary intention clear in all of Paul’s letters—and the church Father’s own tomes.

What if the Gospel of Luke was crafted to answer this question of the role and place of women in this new religion? If we read it that way, subtly, what do we find out?

What we do know is that with the abundance of women in Luke, this gospel has been fundamental to how women have been viewed and treated throughout Christian history—and Western civilization for the past 2,000 years. Thanks to the depth of scholarship by courageous feminist theologians, the truth has risen to the top. Namely, that Luke’s perspective on women has been problematic and damaging from the very beginning.

Truth is scarce in this arena, but we can gather clues in unexpected places if we follow this trail.

This brings us back to Marcion again. Marcion’s gospel hints that original material used by Luke’s author, or possibly an older version of Luke itself, placed women in an even more positive role. Writes scholar Markus Vinzent, “The move from [Marcion’s gospel] to Luke highlights a shift from the authoritative role of women to that of men at the expense of women.”

Vinzent points out that Luke differs from Marcion in subtle ways. Luke minimizes the connection between Jesus and “two women,” who are later identified as none other than Mary Magdalene and Joanna. Further, there are contrasting elements between Marcion and Luke’s gospels accounts of the female resurrection witnesses. Writes Vinzent, ”Luke seems to need Peter to confirm the story of the empty tomb, which reduces the standing of women as witnesses even further.”

This is brushing the surface–as we are certain that even more hidden puzzle pieces exist in the mysterious muddle of biblical scholarship around Luke and women.

The “devil” is in the details and thankfully, renegade feminist scholars over the last few decades have worked to uncover the truth about Luke’s women with grit and brilliance.

Scholar Mary Rose D’Angelo points out, beyond the infancy narratives, where Mother Mary and Elizabeth appear as passive, submissive vessels, no woman speaks in Luke, except to be corrected by Jesus. Throughout Jesus’ stories in Luke, even though women appear as part of the scenes, they do not bear responsibility within the movement, notes Jane Schaberg. Luke’s women are never actively preaching, teaching, healing, or praying, instead, they are silent and receptive, having “chosen the better part,” writes Barbara Reid in her book by the same name.

What, then, are the features Luke documents around Mary Magdalene—and how have they impacted her legacy?

Naming Magdalene

Let us return to Pope Gregory’s thesis and untangle it. As we shared in The Greatest Lie Ever Told, on why he painted Mary Magdalene as a prostitute, Gregory said in Homily 33, 591 AD: “We believe that this woman [Mary Magdalen] is Luke's female sinner, the woman John calls Mary, and that Mary from whom Mark says seven demons were cast out."

Although there are three separate characters here (and he references three different gospels), the entire case he builds for “Mary as prostitute,” and all of her accused negative attributes are derived from Luke’s account, solely.

It is important to briefly address Mark and then John before focusing on Luke’s sinner and Mary Magdalene.

Though Gregory references Mark as the gospel associating Mary with “the seven demons,” this reference to Mary in Mark comes from a curious part of the gospel—the added endings. Most scholars agree that Mark originally ended at verse 16:8. Meaning that Mark 16:9 where it states “when Jesus rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had driven seven demons” was tacked on later, likely copied from Luke.

Gregory references “the woman John calls Mary”—this is Mary of Bethany who is never explicitly called Magdalene found in the gospels of John and Luke, but with differing stories. Tradition at the time held that Mary of Bethany was Mary Magdalene, a point of contention debated by scholars to this day, and one we will address in depth in future writing.

Gregory includes Mary of Bethany, who he and his audience believes is the same as Magdalene, because Mary of Bethany is John’s anointing woman. What Gregory is trying to do is to draw a direct line between Mary Magdalene, John’s anointing woman Mary of Bethany, and Luke’s anointing woman, known as “the sinner.”

To return to Luke—we find Mary Magdalene associated with negativity, off the bat. In Luke 8, it is written that there are “some women who had been cured of evil spirits and diseases” following Jesus, including “Mary called Magdalene from whom seven demons had come out.” But to the ancients, “demons” did not mean “sins” explicitly—there are many possibilities to this term.

Demons could have meant an illness, a poison, or a purification initiation of high spiritual authority, especially given the sacrality of the number 7. Whatever Luke meant by the inclusion of this label, it was amplified by Mark’s forged ending, a negative connotation stuck that followed Mary Magdalene.

Many do not realize that the “seven deadly sins” do not exist in the Bible—just like “Mary as prostitute.” Rather, these were ideas floating around in early Christianity formally codified into doctrine by none other than our Gregory.

The Sinner Who “Loved” The Most

It is significant that the reference in Luke 8 to Mary Magdalene and her “seven demons” directly follows the ending of Luke 7, where he tells the story of the unnamed sinner who anointed Jesus as Christ.

Yes, “Christ” means “anointed one,” which is why we must pay attention to these anointing scenes and women in particular. Many believers and even scholars gloss over the discrepancies between the four anointing stories. A sacred ritual enacted by a woman across the canonical gospels, it is a significant moment in which the smallest details hold the shiniest treasure–in Luke, especially.

Gregory, for one, takes the feature of Luke’s story of the anointing woman and expands upon them, generously.

The holy oil the woman uses for anointing Christ becomes perfume in Gregory’s eyes, used to “give her flesh a pleasant odor.” Her demonstration of love becomes “coveted earthly eyes” and her show of devotion “penitence.” A detailed read of Homily 33 borders on eroticism in the way Gregory spins the components of Luke 8 into the lies that would follow Mary Magdalene for 1400 years, mirroring the Song of Songs, a romantic poem of the Old Testament long associated with her and Jesus.

If we step back for a moment and question the entire scene, the obvious issues become apparent.

Why would such a sacred act as the anointing of Jesus as “Christ” be done by an anonymous woman, let alone a “sinner”? Is this not a ritual performance reserved for male priests or other more favored apostles? With such a great value to this moment in Jesus’ story, why would she remain nameless in Luke, Mark, and Matthew?

How does her anonymity pair with the fact that in Mark and Matthew Jesus proclaims of the anointing woman: “throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her”?

Gregory does not seem to mind that in Luke’s text, Jesus defends and forgives her, a subtle foreshadowing to his ultimate act of forgiveness on the cross. Jesus says, “therefore, I tell you, her many sins have been forgiven—as her great love has shown. But whoever has been forgiven little loves little.” The person he is addressing in this scene is another crucial clue—only in Luke, Jesus speaks about the anointing woman directly to Peter, the apostle who founded the Church.

As Reid points out, this section of the text had no title in the original Greek version, but later English Bibles have never failed to mark it with words highlighting the negative qualities of the anointer. Why, asks Reid, would we not perceive this woman the way Jesus did? A most accurate description of Luke 8, when perceived with eyes of compassion, might be “A Woman Who Shows Great Love.”

Hidden in Plain Sight

When we shift our perspective to the positive around the anointing woman, Mary or not, it breathes new life into an old story that makes it hard to overlook the problematic nature of Luke’s narrative.

Again, the minute aspects of a story that are easy to gloss over are where the author’s beliefs about women—and possibly Mary herself—come into sharper focus.

Small details stand out, like how in every other canonical gospel Mary Magdalene is noted by name to be present at the crucifixion, except in Luke which leaves her and all specific female names out. But there is another anointing scene in the gospels that is arguably more important, in which Jesus’ followers go looking for his body and find that he has been resurrected, and it ties to all of this.

If read holistically, the anointing woman scene foreshadows what’s to come in a very direct sense.

In Matthew, Mark and John, the anointing woman is referred to as the one who will perform the burial anointing after Jesus death. Luke omits this detail—the burial anointing is not mentioned in the anointing scene, standing in stark contrast to the other three gospels. However, Luke does name Mary Magdalene as one of the women at the burial anointing and amongst the women receive the “good news” of Jesus rising from the two men at the tomb, presumably angels.

For a skilled storyteller, this is a curious discrepancy from two gospels that most scholars believe are earlier. Matthew and Mark have Jesus himself saying that the anonymous anointing woman will prepare him for his burial—and none other than Mary Magdalene is who shows up to do the burial anointing in Luke’s own account.

This connection was not ignored by the first Christians—it is likely a significant reason that Pope Gregory assumed that Mary Magdalene was one in the same with the anointing woman and Mary of Bethany.

A final detail to note in this burial scene—in Luke’s gospel, when Mary Magdalene and the women have received the good news, they are not believed by the other apostles, “because their words seemed to them like nonsense.” For Luke, it was only when Peter ran to the tomb that their circle began to understand what had occurred to Jesus’ body and spirit. No mention of the women’s inadequate word is recorded by the authors of Matthew, Mark, or John.

As the evidence piles up, it becomes clear how feminist scholars like Barbara Reid have concluded that when it comes to women, Luke is “ambiguous at best, dangerous at worst.”

Even in spite of this, the framework in Luke remains open for anyone with a positive lens on Mary Magdalene to reimagine her, if willing to transcend the conditioning of the belief systems we have been given.

Magic in the Margins

Swinging the pendulum as far as possible is the common response when we have realizations about an idea or story we once held to be true to us. How easy would it be to blame and vilify the author of Luke for the negativity surrounding Mary Magdalene and the minimization of women in the Church?

Feminist theologians have done a beautiful job of balancing the harder truths with a liberationist approach to hermeneutics—a fancy way to say that it's possible to empower women without throwing away the text, and with it all the positive culture, traditions, beliefs, and stories it contains in it.

While it is traditionally taboo to question the veracity of the Bible in this way–to ask questions about the intention and imperfection of stories first held in people’s memories, then spoken in communities, and eventually captured and woven into scripture.

Yet, when we consider the pathway the story of Jesus would have taken in a practical way, with a human lens, another possibility arises.

What if earlier oral traditions, that may or may not have made it into text, held positive portrayals of all women across Jesus’ story?

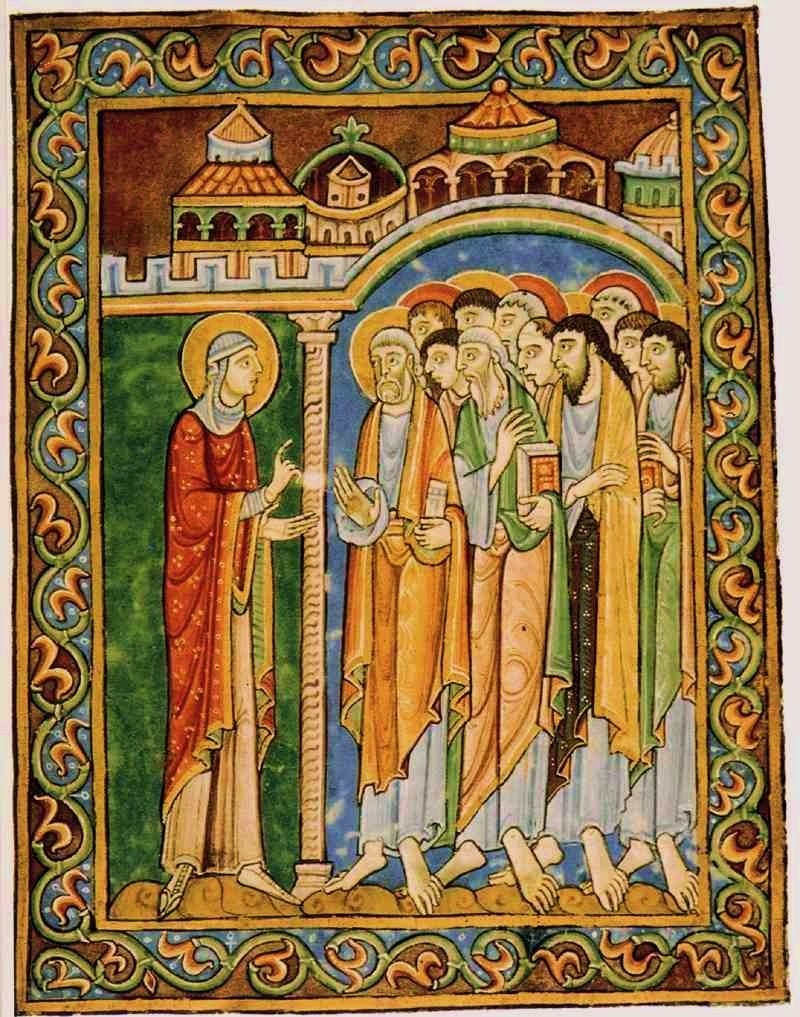

As depicted in the earliest Christian art and non-canonical literature, women were active leaders in sharing the good news with communities across the Levant, Egypt, the Greco-Roman world, even into Western Europe—as we discussed in Goodness in the Garden and Women Sex & Sin.

What if the quantity of women described in Luke’s narrative is a remnant of this truth?

Could it be that while the women were not completely erased, a sketch remains though their goodness and mastery redacted from the story?

We recognize that this is a possibility that sits on the fringes, or margins, of Christian thought. So often we turn away from questions like these out of fear that opening up to other historical narratives might suck all the good out of our cherished beliefs and stories.

The magic Luke creates is undeniable—from his synchronistic conception scenes followed to the precious humility of the nativity, the birth of a king into unexpected circumstances. Careful analysis does not need to negate all the good so many find in this gospel, and any of the other biblical stories.

Every single one of us has a lens on the truth—it is natural that we narrate the plot of our lives through a perspective colored with beliefs and experiences. We only deceive ourselves and others when we fail to take that filter into consideration in our own unique processes of discernment.

If we choose to remain bound by the perfection of what we are told is the only allowable truth, we miss the opportunity to cultivate compassion and gain wisdom from what we find in the messy margins of this human story.

To greet new perspectives on Mary Magdalene, we must enter this liminal space and the potential these realizations have to bring us on a trail of discovery where there is magic at every turn.

*John’s portrayal of Mary Magdalene we will begin to dive into next week!

**We use the word “he” here, as another way to refer to Luke’s author, but it’s imperative to note that the gospels may have been written by groups of authors. This is a common theory around John’s gospel. Irregardless of it simply being another possibility, the truth is that all the gospels were written by many people in that each was edited, redacted, and naturally influenced by the scribes who copied them over time. This too we’ll discuss more in depth in our next article.

Share with your Mary Magdalene friend

We would love it if you would share The Magdalene Thread with a friend who you know would resonate with our message or who just adores Mary Magdalene. We are so grateful for your readership and support!

Source List

Against Heresies, St. Irenaeus of Lyons

Choosing the Better Part? Women in they Gospel of Luke by Barbara E. Reid

Did Paul Write Colossians? by Bart Ehrman (2020)

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

The Gospels are Finally Named! Irenaeus of Lyons by Bart Ehrman (2014)

A homily of Gregory the Great and Mary Magdalene (Text of Homily 33) by Roger Pearse (2020)

How We Know Acts Is a Fake History by Richard Carrier (2023)

Holy Women in Early Christianity by Markus Vinzent (2021)

Mary and Early Christian Women: Hidden Leadership by Ally Kateusz

Mary Magdalene and the Women Disciples in the Gospel of Luke By Barbara Reid

A New New Testament: A Bible for the Twenty-first Century Combining Traditional and Newly Discovered Texts, compiled and edited by Hal Taussig

The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene: Legends, Apocrypha, and the Christian Testament by Jane Schaberg

So: Was Luke Luke? by Bart Ehrman (2020)

What is distinctive about Luke’s gospel? by Ian Paul (2021)

Read our full source list, updated regularly, here:

Living Resources on Mary Magdalene

Welcome to a treasure trove of diverse perspectives on Mary Magdalene, and all her legend and legacy touches.

Thank you for this amazing scholarship. I am fascinated!

Great read, thank you!